Children and the Common Good

A Postliberal Account of Children, Immigration, and Thanksgiving

The existence of children requires Common Good postliberalism.

Perhaps the incoherence of the liberal account of children provides no greater sign of its inadequacies.

Children led me into postliberalism. The early Stanley Hauerwas’s astute ethical observations pointed the way.

Recently Zena Hitz has expanded my understanding of the importance of children — and grandchildren. Hitz represents one of the great gifts to the intellectual life in the United States today.

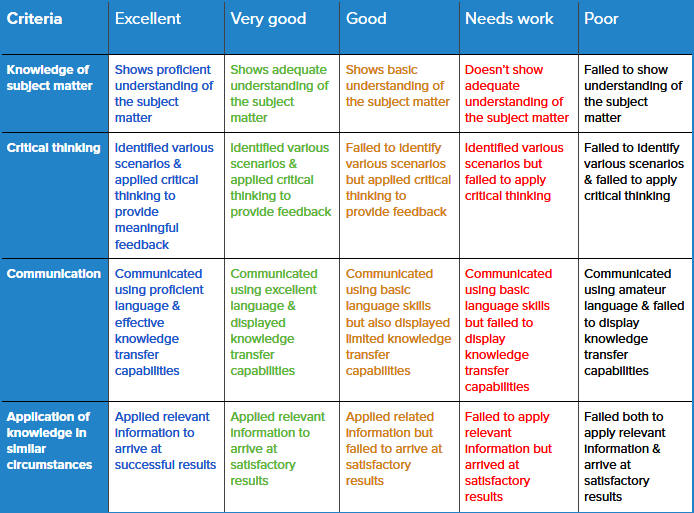

Her Lost in Pleasure: The Hidden Pleasures of an Intellectual Life (2020) is itself a pleasure to read. Her A Philosopher Looks at the Religious Life (2023) overflows with wisdom — and Wisdom. Her founding of the Catherine Project represents an ever-growing sign of hope for a world that reduces education to rubrics like the production of Spacely Sprockets:

Liberatarian/progressive education undercuts the formation of good thought/the executive function of children. Such an understanding of education displays the horrible reductions inherent with liberal theory — and its inability to educate human beings well.

This is how the so-called “meritocracy” now works. And we wonder why the educational formation of children and young adults has failed us.

Liberalism forms children/young adults in a specific way. Liberalism teaches children to dissolve the “involuntary relationships” between family and regions. We can see the results around us in the social fragmentation that plagues us all.

Hitz reminds us of a richer, truer view of children — and their philosophical importance. I would like to explore her explication of the importance of children and the contrast to liberal formation.

As the Librarian of Celaeno has recently written, the goal is “Adopting ideas neither older nor newer, but higher and better.”

I. Liberalism looks to raise children into autonomous adults who can make up their own mind about who they should their time with.

Why have children?

The question has become existential across many societies today. Liberalism places the private good above the public good. This, of course, means that children serve the private good of the parents — until they don’t. Parents provide the free labor in return to raise an autonomous individual who can chose their own private good for her or himself. Invest well, and you will receive your reward in old age.

Birth technologies mean that parents think that they “chose” a child. Parents make a “rational choice” whether or when to have a child or not — and how many. Society forces parents to calculate an optimal time and number between economic stability and the “pleasures” of a child. For the wealthy, genetic selection companies provide a means for parents to chose a boutique child.

Education becomes a means by which one can insure that the child can obtain autonomy — i.e. obtain wealth that provides the optimum number of choices for the individual. If one does a good job from the perspective of the child, when the child becomes an “adult,” the child will “choose” the parent as part of the “child-turned- adult” life style enclave.

“Choice” governs the whole process. One “choses” to have and rear a child. Effective parenting helps the child to make “good” choices. When a child reaches a societally-determined age (i.e., 18), the autonomous young adult can make her or his own rational choices. Society can legally hold the individual accountable.

A parent raises a child to become a stranger — an autonomous individual that parents hope will give a return on investment to allow the one time parent to have meaningful interactions with their grandchildren.

The liberal view diminishes children and adults. It cannot account for the complex and rich and functional/dysfunctional results of families, nuclear and extended.

II. Children give a society a reason to work for a common good — and the eternal Good.

When one places the priority of child rearing on the individual good, one cannot give a coherent empirical account of children, nor attend to a child’s developmental and adult requirements. The biological and developmental unreality of liberal account reveals much about the dysfunctions that liberalism produces.

One must start with the good of family as a social good within a common good — that opens to the Eternal Good. A coherent and truthful understanding of children requires one begin with the social good and receive children within the familial good. The goal becomes good mutual dependencies of all, not autonomy.

Zena Hitz reorients us away from a liberal view. She asks a simple question: “How much of our life or work is about our children?” PLR, p. 31).

The liberal account of children diminishes our ability to answer such a question truthfully. Hitz points us to a fictional dystopia: “Consider a world without children, as portrayed in the 2006 film of P. D. James’ novel, Children of Men, directed by Alfonso Cuarón. In the film, every human on earth was suddenly stricken infertile twenty years earlier. The youngest person on earth is twenty-one years old. The schoolyards are empty, and endemic violence is narrated by a competing array of propaganda machines. Only fanatics seem to have projects of any scope. Life under these circumstances appears utterly pointless” (PLR, p. 31).

Such a situation almost describes North Atlantic society’s low birth rates. I spoke briefly with an administrator of a local high school recently. When the new school opened less than 20 years ago, it welcomed 2900 students. Today it is nearly half the size: an enrollment just over 1500 students. Educational debt and high mortgages take priority over children for young adults, even those seeking marriage. Similar demographic realities now structure society, largely unseen.

She continues to reflect upon the importance of children: “The threat the scenario poses is not [just] to the childless, but to any of us. The lives of childless persons like myself have meaning thanks to other people’s children. I am a teacher. I pass on to young people the habits of mind I learned myself when I was young. They shall (I hope) replace me as teachers of the young when I am no more. If there are no young people, there is nothing and no one to teach; those habits of mine will die with me and my contemporaries. So too with any endeavor: starting a company, planting a farm, building a skyscraper, lobbying for justice” PLR, p. 31).

Any human institution requires an intergenerational mixture of humans and nonhumans. Civilization itself requires intergenerational admixture. As Hitz reminds us, without children, “those habits of mine will die with me and my contemporaries.”

Children play a required role within the overall good functioning of society. Human beings never become autonomous. Human brain development never ceases; it reaches biological “maturity” around age 25. Families continue to play a role in development. Humans remain a species who biologically live beyond the ability to reproduce. Such extended life periods allowed younger generations to survive and even thrive. Development does not suddenly “stop” with adulthood, nor do elderly interactions between younger generations stop. Human beings naturally live and require intergenerational overlap.

Specialists in formation emerge developmentally or educationally — often developing amazing, innovative, and rare specialized skills. Such “specialists,” however, presuppose both the historical work of previous “generalists” and the continuing presence of “support persons.” A specialist is the last thing from a meritocratic individualist; others provide her or his ability to specialize. The good of persons always and every where requires the common good.

And the common good itself only can sustain it from implosion through remaining suspended from the Eternal Good.

Wendell Berry once wrote, “I am speaking of the life of a man who knows that the world is not given by his fathers, but borrowed from his children; who has undertaken to cherish it and do it no damage, not because he is duty-bound, but because he loves the world and loves his children” (The Unforeseen Wilderness : An Essay on Kentucky’s Red River Gorge, p. 33). Such a saying encapsulates the question that Hitz asks. Children provide a requirement for human life to flourish.

One can find scarcely a more succinct refutation of the liberal account of children.

III. All Common Good policy ultimately signs towards the flourishing of future generations within a specific society.

The plummeting of the birth rate, the economic damage done to the young through liberal rent-seeking, the inability of women to find “marriageable males” all show the futility and failure of liberal political theory and practice. The liberal elite, however, reduce the issue to libertarian economics and the meritorious preservation of their classes’ own social, hierarchical advantage.

Only from the advantage that hierarchy provides can a liberal press non-hierarchies upon others.

The largest social, political issue of North Atlantic societies, immigration, has resulted. Nations must control their own borders for the common good — a non-competitive common good that also enfolds others nations and their need for human beings. Seen correctly, immigration policy ultimately manifests itself in relationship to family policy — and the place and flourishing of children.

Philip Pilkington has brilliantly analyzed the relationship between liberalism and immigration. Pilkington speaks of Great Britain but his observation works for other North Atlantic societies as well. The quote is worth slogging through its length:

“Because their ideology is based on total equality, liberals think of human beings as interchangeable. For this reason, they cannot see why importing large numbers of people from other cultures might be politically and socially destabilizing. But just because liberals were ideologically blind to political and social challenges to mass migration did not mean that these challenges failed to make themselves felt. Indeed, they made themselves felt forcefully: immigration, especially in Europe, became the largest and most contentious political question during the late stage of liberalism. Liberals were completely taken aback by this development and started to view large sections of their own populations as being morally retrograde. This led to an increasing isolation of the liberal elite from their societies. . . . [Population growth dependent upon immigration] was recognized by the liberal political elite as being necessary for economic growth. By the early 2010s, there were more people being imported than there were new Britons. And by the early 2020s, the natural increase in the population – that is, births minus deaths – was close to zero: all net growth of the British population was through the importation of people” (CGL, p. 141).

A world without children, as Hitz reminded us, empties our lives of meaning.

In liberalism parents ultimately raise children to become social strangers. A liberal cannot understand what difference it makes if the stranger is biological or non-biological? Why not reduce the costs to the elite for the raising of children to non-Northern European countries which raise them cheaper and appropriately skilled for low skilled labor. Like cheap oil from Iraq, government sponsored immigration can lower the costs for population growth and ensure an ongoing rise in GDP.

But human beings just don’t work that way. Count it another liberal denial of the natural hierarchies. People, outside the propaganda of the liberal institutions of deep state, mainstream media, and academy, know the difference between children and immigrants. They know the difficulty that liberal institutions have forced young adults and their children into. People have particular ties to the well-being of their kin and region. In other words, people know that an immigrant is not merely an equal autonomous individual like a grown child. That is nothing against an immigrant. It’s just that biological ties work differently — you can blame oxytocin, if you’d like. Parents have attachments to the good of the next generation, even if they must politically and publicly deny such attachments in the name of “equality.”

Common good political theory and policy must seek the flourishing of children as its first and foremost goods. The state must pursues peace, justice, and abundance for the flourishing of children, or it will short-circuit itself.

This is why a civilizational good precedes all other goods — and why liberalism cannot provide a civilizational stability for a world into which the fertile might find it easier to raise children.

Let me repeat the key point for emphasis:

Common good political theory and policy must seek the flourishing of children as its first and foremost good. Only in light of children, does its temporal pursuit of peace, justice, and abundance maintain its coherence

Libertarianism nor progressivism can get us there. Convincing dependent human animals that they are autonomous reeks of gross political propaganda. It’s time that we begin to prioritize the good of families and children in our political theory and policies.

IV. Conclusion

This coming week represents a time when in the United States, extended families gather for a meal — citizens of the United States call it, “Thanksgiving.” Such gatherings will have their challenges. Just because we note the importance of children and families within a common good framework does not mean the we should romanticize and valorize extended families. Such extended familial groups have given us gifts undeserved; they have failed us. But they also are us. One of my old sayings is, “God gives us families to give us something to work on the rest of our lives.” Old irritations will arise as familial roles, now superseded by adult lives, re-emerge unconsciously. Old pains and wounds from involuntary relationships arise.

Perhaps that is part of the good of extended families — and even friends to whom we open the family to — for family’s have the ability to expand to welcome the genuine stranger because its members are family, not strangers. Even in face of families obvious, even traumatic, limitations, they also provide the context for truthful healing that intergenerational events can provide — even wisdom passed down through the bustle of food preparation and the mess afterwards.

And don’t forget that we call the day, “Thanksgiving.” We name it such for the ongoing gift of life in this temporal order.

Such a national “Thanksgiving” opens Christians to the “Great Thanksgiving” — the Eucharist, receiving the sacramental Body and Blood of Christ to be made part of the ecclesial Body of Christ in preparation for the beatific vision. The relationship between the common good, a temporal reality that opens to the eternal Good in God appears in the practice.

The General Thanksgiving prayer in the ACNA’s daily office reveals the common good logic:

“We bless you for our creation, preservation, and all the blessings of this life;

but above all for your immeasurable love in the redemption of the world by our Lord Jesus Christ, for the means of grace, and for the hope of glory.”

The temporal common good, achieved by reason, opens to and finds itself suspended from the Eternal Good found in the hope of Glory. The temporal good remains ordered to the eternal Good, even if the state cannot and should not require persons to participate in the “Great Thanksgiving,” the Eucharistic feast, to celebrate the national Thanksgiving.

We celebrate the national Thankgiving to enfold children into a broader, familial system from which they have originated — involuntarily. Adults give thanks for children — both adult children and the generations that follow from the surviving matriarch or patriarch. The youngest disrupt; their parents labor hard; the elder generation look on with remembrance and recognition that without them, their own life would become greatly diminished.

Liberal political theory cannot account for such gatherings; but common good theory can. Both the turmoil and the peace of this week give witness to the truth that we do share a non-competitive common good — and it opens up to the eternal Good.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Thank you for reading these reflections. I hope that they spur you to your own reflections. Perhaps some day I can share about the Bridenbaugh Thanksgivings in my Uncle Roland’s basement. They always involved the wonders of his air-driven Player Piano and the tunes that it heartily plunked out. I received many uncompensated for gifts from those family gatherings, including the glorious, caloric feast of Pennsylvania Dutch cooking. My cousin Pam made the worlds best “Old Fashion Cream Pie” that no doubt still clogs my arteries.

It would help spread the news of this Substack through liking and reposting it. We are battling against the liberal marinade. One runs up against the constraints of the Substack algorithm. In a world that sees children as a “choice,” we need to out-narrate the liberal marinade through more truthful accounts — and see the horrible costs of liberal political accounts on those who we love in this temporal world, most and best — despite our deep failings.