The Liberalism of "Conservative" American Evangelicalism

Why "Conservativism" Loses to "Progressivism" Before the Contest Ever Starts

It was before the Moral Majority. Before Roe v. Wade. Before James Davidson Hunter named “the Culture Wars.”

I participated in a then dying 19th and 20th century American institution — the Camp Meeting.

I was only around eight years old. The district of our church-like fellowship had rented a large hall in Dayton, Ohio. The district did not own a campground with a “tabernacle,” pit toilets, and small, plywood cabins. Multiple congregations had gathered and moved inside. The “meeting,” as it was called, took place with climate control and running water. Chairs had replaced hard wooden, backless benches.

Like I said, camp meeting was a dying institution.

Someone had spread saw dust in the aisles. The sponsors wanted the authenticity of earlier camp meeting/revivals. But with flush toilets, climate control, and, by all means, no hard wooden, backless benches. Authenticity has its limits.

The service began with special musicians. The people joined singing 19th, early 20th century hymns. A few older saints soon began to jog slowly in the aisles. White hankies waved in the air. Shouts of “Glory” filled the auditorium. Others followed in the geriatric competition.

“Camp Meeting Slow Jam.”

An official announced the offering to raise funds for the hall, the sawdust, the special musicians, and the evangelist. A male singer arose on the side of the large platform. Hair gel held his gleaming black hair in place. The choir rose behind him.

I still remember the song:

“In a harbor, there stands a lady.”

The crowd/congregation erupted as the song progressed. More hankies appeared. Like Terrible Towels at a Steeler’s Play-Off game.

Ordered chaos ensued. An unwritten choreography took over. Geriatrics stood, ran slowly in the aisles, and shouted. It was the expected camp meeting behavior. Those “moved by the Spirit” disturbed the saw dust in the aisles. The crowd crescendoed with the music.

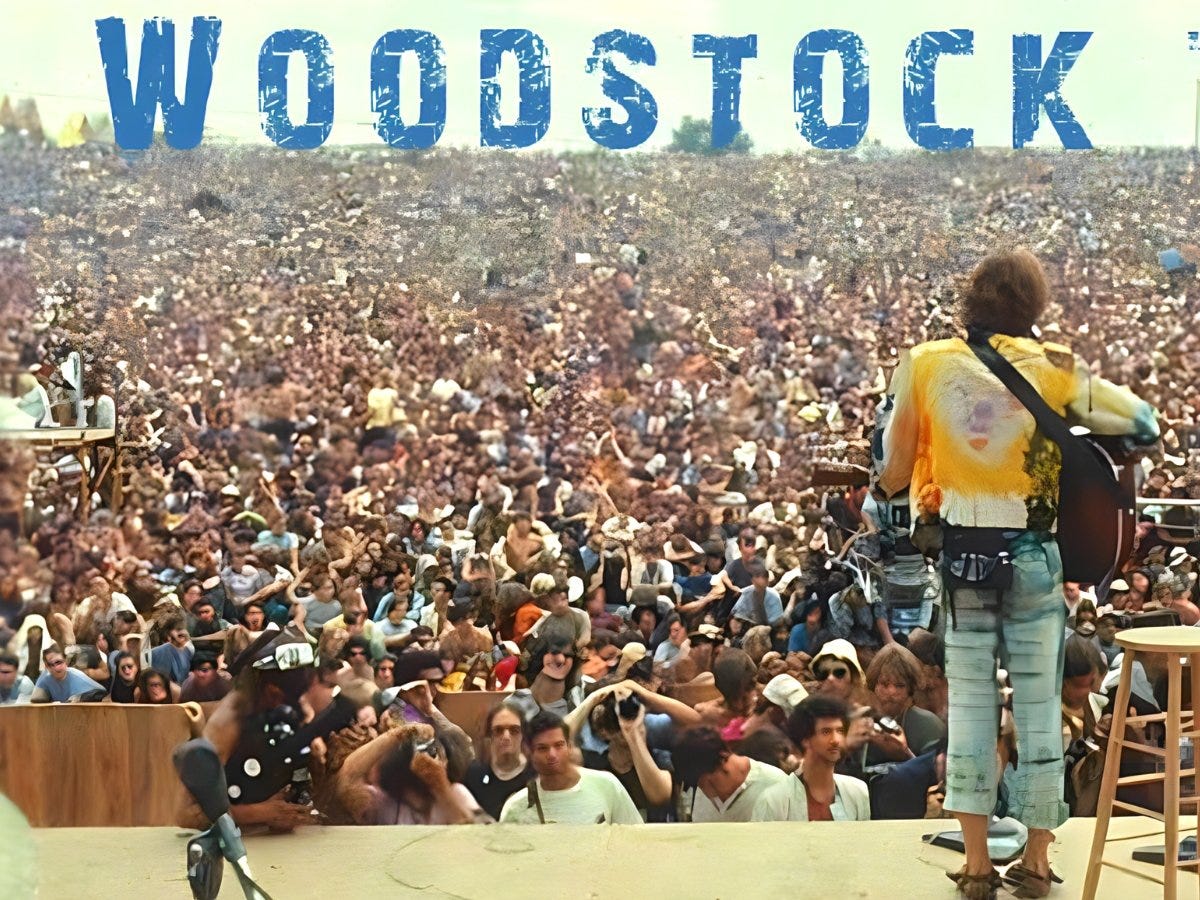

The camp meetings descendant, Woodstock remained a few years away.

The song? The Statue of Liberty.

In New York Harbor stands a lady

With a torch raised to the sky

And all who see her know she stands for

Liberty for you and me

And I'm so proud to be called an American

To be named with the brave and the free

I will honor our flag and our trust in God

And the Statue of Liberty

On lonely Golgotha stood a cross

With my Lord raised to the sky

And all who kneel there live forever

As all the saints can testify

And I'm so glad to be called a Christian

To be named with the ransomed and whole

As the statue liberates the citizen

So the cross liberates the soul

Oh, the cross is my Statue of Liberty

For it was there that my soul was set free

Unashamed I'll proclaim that a rugged cross

Is my Statue of Liberty

Unashamed I'll proclaim that a rugged cross

Is my Statue of Liberty!

You can hear the Gaither Family Singers version here.

Why did the crowd/audience/congregation get so amped that night nearly sixty years ago? Their response expressed their deepest commitments:

American conservative evangelicalism places a Protestant Christian veneer over its deeper commitment to liberalism.

I. The song expresses its commitment to its deepest Good: “Liberty.”

The word “liberty” works differently according to its unspoken linguistic background. I have earlier looked at Isaiah Berlin’s analysis of two types of freedom. Quentin Skinner has gone beyond Berlin. He examined the genealogy of “liberty.” “Liberty” works differently in its classical, neo-Roman use from its later use in liberalism.

The neo-roman theorist “generally make it clear that they are thinking of the concept in a strictly political sense. They are innocent of the modern notion of civil society as a moral space between rulers and ruled, and have little to say about the dimensions of freedom and oppression inherent in such institutions as the family or the labour market. They concern themselves almost exclusively with the relationship between the freedom of subjects and the powers of the state. For them the central question is always about the nature of the conditions that need to be fulfilled if the contrasting requirements of civil liberty and political obligation are to be met as harmoniously as possible” (Liberty before Liberalism, p. 17). These theorists asked freedom means for a particular social institution: how does it remain independent of outside control so that it can determine the Common Good?

Liberty in the neo-Roman, classical tradition means independence from the control of another group. Coercion is not its main concern; the state does not undertake the responsibility to give each individual autonomy. The state commits to the common good of its citizens. Loss of “liberty” leads to a loss of the common good.

“Liberty” works differently within liberalism. It requires a more expansive power of the state: “One of the prime duties of the state is to prevent you from invading the rights of action of your fellow citizens, a duty it discharges by imposing the coercive force of law on everyone equally. But where law ends, liberty begins. Provided that you are neither physically nor coercively constrained from acting or forbearing from acting by the requirements of the law, you remain capable of exercising your powers at will and to that degree remain in possession of your civil liberty” (p. 5).

Liberty in liberalism means the absence of coercion. The state frees individuals. You can live as an autonomous individual to achieve your own personal good. The state “liberates” one from family, from tradition, from geography, from children, from any social ties that may encumber you. No common good exists-by definition (except, of course, the “freedom of the individual”).

The question becomes:

Which represents the Statue of Liberty from the song? What type of “liberty” does the Roman goddess give “for you and for me”? Which “liberty” makes the Christian “proud” to stand under?

The song only works with the liberal understanding of “liberty.”

The Statue of Liberty “stands for” the state that “liberates the citizen.” From what? From coercion. From a common good. So that others can esteem the individual as “the brave and the free.” No social group exists in the song. The Statue of Liberty represents the government that allows the individual to pursue her or his own private good.

Supposedly “American conservative evangelicalism” commits to American nationalism. Nationalism, however, has a deeper reason. The (Protestant) Christian commits to nationalism because the state’s liberalism “frees” the individual to do what he or she desires. No institutions stand between the individual and the state. The state frees from such meddlesome groups.

Bowling alone.

American Evangelical Conservativism is Liberalism.

II. The same liberty works in two different spheres that do not interpenetrate.

One finds a “division of spheres,” a parfait of liberty, so to speak:

The state frees the body from coercion; the cross frees the soul from the coercion of sin.

A univocal analogy between the realm of the state and the realm of the cross exists:

As the statue liberates the citizen

So the cross liberates the soul

One liberty, two independent realms.

The song presupposes a dualism of body and soul. The state, however, has complete control over the citizen — the body. The state protects the citizen from coercion that others might place on them.

The cross declares one forgiven by God as a legal fiction. This ensures an individual’s eternal life. God attributes justice to the individual through Jesus’ death on the cross.

The song knows no “suspended middle.” Two distinct realms exist. The physical, public realm exists under the state’s protection. This is the realm of “knowledge.” No Good exists in this realm except the good of the autonomous individual to choose his or her own private bodily good.

The state, however, does not intervene in the second realm, the spiritual realm. It is the private, the realm of the soul and of faith. In this realm one is “named” — outside one’s body or reality. (Yes, one finds here that 1960s already embraced a realm of social construction that defines “reality” for the individual).

The song “Statue of Liberty” celebrates the ontological division that liberalism demands. It takes an anti-Christian political theory and creates a post-Christian form to accommodate to it. It celebrates an individual Christians rightful place within a society shaped by liberal political theory.

Or to restate my argument again:

American Evangelical Conservativism is Liberalism.

III. “Liberty” becomes the only transcendental good that unites citizen and soul, body and spirit.

The song establishes “liberty” as the only transcendental good for human life:

“Unashamed I'll proclaim that a rugged cross

Is my Statue of Liberty!”

Liberal liberty remains the Real. The Statue of Liberty helps one remember the Real, kind of like the Lord’s Supper helps one remember the cross. But only one liberty exists. The cross manifests the same liberty as the Statue of Liberty for each and every individual.

Note that song personally identifies the cross one’s own, personal Statue of Liberty. Liberty results from an act of the will. The will can name its own personal good without regard for a common good. One can name your own good as you want! Try substituting a different image in the song with whatever you want. It will work!

Try this one:

“Unashamed I'll proclaim that an old gopher hole

Is my Statue of Liberty!”

One more, just for good measure:

“Unashamed I'll proclaim that my grandfather’s cigar

Is my Statue of Liberty!”

It works!

Pick the symbol most endearing to you. It makes no difference as long as you don’t impose it on me. It tells us nothing about reality but only about what you value, how you express your own liberty.

I assume that the writer of the song never read Paul Tillich. Tillich was the most popular liberal theologian of the 1950s and 1960s in the United States. His understanding of a symbol gives a good entry into his thought. For Tillich symbols function expressively, not cognitively or analogically:

“A real symbol points to an object which never can become an object. Religious symbols represent the transcendent but do not make the transcendent immanent” (Tillich, “The Religious Symbol,” Daedulus [1958], p. 5).

The symbols of the Statue of Liberty and the Cross express the same transcendental reality, liberal liberty. The symbols don’t make “liberty” present in the world, but they point to it as a means of expression of the transcendental reality. Like liberalism the “religious symbol” belongs to a different realm than public reality, a realm of faith that stands outside the realm of reason.

American Evangelical Conservativism is Liberalism.

IV. Conclusion

The hankie brigade that evening celebrated the transcendence of liberal liberty. The liberty-rollers thought life unfolded in two distinct realms: the citizen (body) and the soul (Spirit). They, with the song, placed the two in juxtaposition so that the real transcendental, liberal unity, became celebrated as their most important “Ground of Being” (to wax Tillichian again). The pseudo-camp meeting (no perspiration allowed) represented a celebratory political rally under the guise of a voluntary Protestant meeting. Liberal Liberty elicited the depth of emotions from the audience.

The song is unintelligible outside mainline American culture of the 1950s. The explicit reference to “in God we trust” did not take effect on USA currency until the 1950s. Liberal Christian nationalism versus “godless communism” provided the rhetorical trope to justify the Cold War. Only Christian nationalism as a political commitment to liberal liberty could resist the spectre of the USSR.

Don’t mistake that crowd for progressives. There wasn’t a Hubert Humphrey voter there. In the liberal Overton Schema, the “camp meeting” audience represents “conservatives.” But these conservatives were fundamentally liberals — the beginning of the Reagan revolution. And the Moral Majority. They channeled the liberal expressive individualism into their accommodated individualistic, liberal Christianity. Committed to expressive individualism when they gathered together, they contested its generalization to an overall ethical stance.

The Culture Wars were lost before they even started. Some of those evangelicals should have read Charles de Koninck.

“Conservative” Protestant evangelicalism opposed the rising secular progressive thought in the USA. At the same time, they shared the same presuppositions as their supposed “opposition.” Progressives expressed concern about their nationalism; but their nationalism had a deeper origin in the supposed liberal political theory of the United States. Their nationalism expressed their deeper commitment to a liberal universalism. The so-called “conservatives” only had a rearguard position from the beginning, always in retreat.

They knew nothing of a postliberal common good. And it has cost a whole society ever since, not because they lost, but because they never engaged the real issue.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

American Conservative Evangelical Protestantism, nationalistic or not, long ago accommodated to Cold War liberalism. They posited a voluntaristic, private, relational deity regnant in the private realm. They desired a small, libertarian state governed by public, rational, contractual forces. It is not an accident that evangelicalism hit its highest percentage of adherents in American just after the Cold War supposedly ended. Afterwards, liberals no longer needed to stoke the fervor of the population to legitimate itself — liberalism thought that they represented the only game in town.

Postliberal common good still remains. This Substack seeks to retrieve it, not because it lost intellectually, but because social factors conveniently aided its amnesia.

Thank you for your support. I’m within eleven of reaching two hundred subscribers committed to postliberalism and the common good, join up. We have much more, historical and theoretical and practical, yet to explore.

Thank you. A real confusion exists between the moniker "conservative" for those who are socially conservative but have libertarian economics. I'm not as concerned about AI right now but agree that it merges with transhumanism and becomes bad news. The issue for me is how to build a postliberal common good culture to support the politics that can build within the shell of the old -- like re-building cathedrals -- or just providing maintenance on those that the Church of England wants to get read of now. Thanks for the engagement!

I think you might appreciate this John https://oswald67.substack.com/p/matt-walsh-is-the-gordon-ramsey-of?r=2r3au